October 18, 2025, marks the 40th anniversary of the legendary Nintendo Entertainment System. With this launch, Nintendo didn't just release a console-it created a new reality for the entire gaming industry. What we see today is largely thanks to it. In Russia, almost everyone has heard of it, but not everyone associates this name with Nintendo.

Today, it seems that the dominance of NES was predetermined. But in 1985, almost no one-neither competitors, nor consumers, nor even Nintendo itself-immediately understood what had happened. This is the story of how, in the most unexpected corners of the world, this console became part of the childhood of millions of gamers.

Now, in 2025, a global product is the norm. A simultaneous launch on Steam, App Store, and Google Play makes a game available to billions in one click. If the project is good, and the publisher has managed to tell about it, people start playing it all over the world-from Asia to both Americas. Technically, you can even play in Antarctica. Often-in your native language. Localization, logistics, digital distribution-everything works like clockwork. The world is compressed. Distances are erased.

But those who caught the 1980s remember: none of this existed then. There was no global market-only fragmented, often isolated economies. Each country had its own rules, barriers, and tastes. No cloud servers, no instant updates. A couple of toy stores per city, and one electronics store-and that one mostly for radios and TVs. If you think that's how it was only in the USSR, you're wrong. Electronics were considered fragile, expensive, "not for everyone."

Video games? It was an amusement for arcade halls. And in the USA, the industry crisis struck-the bubble of home games, which inflated in the early 80s, burst loudly, leaving everyone with the feeling that video games at home are a hopeless business, a failed venture.

And, perhaps, if the market had been global in the 1980s, Nintendo would not have succeeded. However, the world was fragmented-and that was its chance.

Japan. 1983

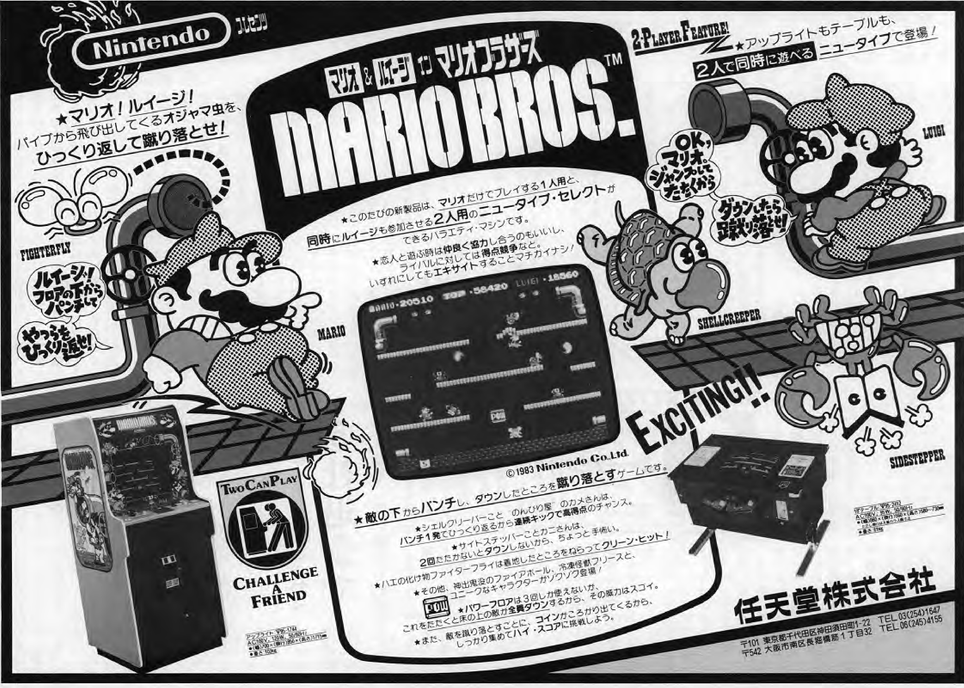

By this time, Nintendo had already established itself as a developer and manufacturer of gaming devices. Donkey Kong was hugely popular in arcade halls, and since 1980, Game & Watch portable devices had sold millions of copies worldwide.

Their influence reached the USSR: Game & Watch electronic games were copied under the trademark "Electronics." For example, the Nintendo EG-26 Egg game was adapted to the motifs of the Soviet cartoon series "Well, Just You Wait!". Since its release in 1984, the game "Wolf Catches Eggs" (official name-"Electronics IM-02") has become the dream of many Soviet boys.

However, Nintendo lacked a "golden mean" in its assortment.

The portable Game & Watch were simple and relatively inexpensive, but their capabilities were limited to one game. Arcade machines, on the other hand, offered rich gameplay but were too complex and expensive for home use.

By the time development began on the future Famicom (the Japanese prototype of the NES), the Game & Watch series had brought the company about 4 billion yen. Arcades, including Donkey Kong, were popular but brought less profit-and, more importantly, did not give Nintendo control over the home market.

Engineers and designers were given a clear goal: to create a home console that was not inferior to arcades in terms of gameplay quality, but at the same time was as affordable as Game & Watch.

The task was not trivial. In solving it, Nintendo was guided by five key principles:

- Affordable price. Set a price so that parents can buy a console for their child without hesitation.

- Software priority. Constantly release a variety of games so that the user always finds something new.

- The role of the designer. Create tools with which even a non-specialist in programming-for example, an artist or game designer-could participate in the creation of games.

- Spectacle. Make it interesting not only to play, but also to just look at the screen.

- Ease of control. Provide intuitive control-with the help of a D-pad and two buttons, anyone could easily control the character without taking their eyes off the screen.

We will not delve into the details of hardware development-although this is also a separate fascinating story. For example, the Zilog Z80 processor, known from the ZX Spectrum 48K/128K home computer, was originally considered. However, in the end, Nintendo chose a different solution. The company's partner-the Japanese firm Ricoh-developed a specialized chip that combined a central processor compatible with MOS Technology 6502 (not Z80), a sound coprocessor, and part of the video controller functions. Moreover, Nintendo used its own developments from arcade machines-especially in the area of sprite drawing speed and animation smoothness.

In response to Nintendo's request for processor supplies at a price of 2,000 yen, Ricoh replied that it would be able to provide such prices only if Nintendo guaranteed an order of 100 million chips. The company agreed-a risky but justified decision.

All these steps sharply reduced the cost of the console and allowed the arcade experience to be realized in a compact home device. In modern terms, Ricoh created a specialized hybrid processor for Nintendo-the predecessor of the very SoC (system-on-chip) that today underlies PlayStation, Xbox, and Steam Deck.

Special attention should be paid to the choice of software media. Instead of cheap audio cassettes (as in Commodore 64 or ZX Spectrum home computers) or floppy disks (requiring a separate drive), Nintendo opted for ROM cartridges. They were more expensive to produce, but provided instant loading, high reliability, and protection against piracy. Although alternatives may have been considered in early discussions, it was the cartridges that made it possible to implement the key principle-"play immediately, without waiting."

In the production of Famicom, everything was saved. Even the choice of the color scheme of the case-dark red and white-was for a long time explained exclusively by pragmatism: there were rumors that those colors of ABS plastic were chosen that cost the least.

However, another version appeared later. According to internal Nintendo sources, the decision to use dark red was dictated not so much by economy as by the personal preferences of the company's management: this shade was associated with corporate aesthetics and even with elements of the wardrobe of top managers of that time. As a result, the final color choice was approved at the highest level.

As for the material of the case, the engineers initially considered a metal case-it was really cheaper. But the prototypes turned out to be too fragile and heavy. As a result, they settled on ABS plastic: it was stronger, easier to process and, despite initial fears, turned out to be economically justified in mass production.

But the lack of removable connectors for gamepads was pure economy. Joysticks were soldered directly to the motherboard, without connectors and connectors. This approach reduced the cost and eliminated one of the potential sources of defects in production. True, in the future this will create a headache for owners: if the wire breaks or the button fails, the repair will cause difficulties. But in 1983, the main task was one thing-to release a console that can be sold for 14,800 yen and at the same time earn money.

It is difficult to roughly estimate this amount in modern money-economic realities are too different. But if you recalculate through purchasing power, then 14,800 yen in 1983 roughly corresponds to 16-17 thousand rubles in 2025 prices. This is comparable to the cost of the Nintendo Switch Lite today-an inexpensive but full-fledged gaming system.

At the time of launch in July 1983, the starting lineup of games included: Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr. and Popeye. This was enough for Famicom to quickly gain popularity. By the end of the year, the console had become a bestseller.

In the future, Nintendo continued to release high-quality games. And Super Mario Bros., released in 1985, further spurred demand.

In the mid-1980s, Famicom in Japan simply had no worthy competitors. Sega released the SG-1000 almost simultaneously, but could not offer either such quality of games or such an ecosystem. The moment was missed.

Famicom conquered the land of the rising sun-and prepared the ground for conquering the world.

USA. 1985

Ironically, there is almost nothing to tell about the main character of our story-the Nintendo Entertainment System, which turned 40 in October 2025. In fact, it was the same Famicom, only dressed up for American taste. Hardware consoles were compatible: the same processor, the same architecture, the same capabilities. But externally-a complete transformation.

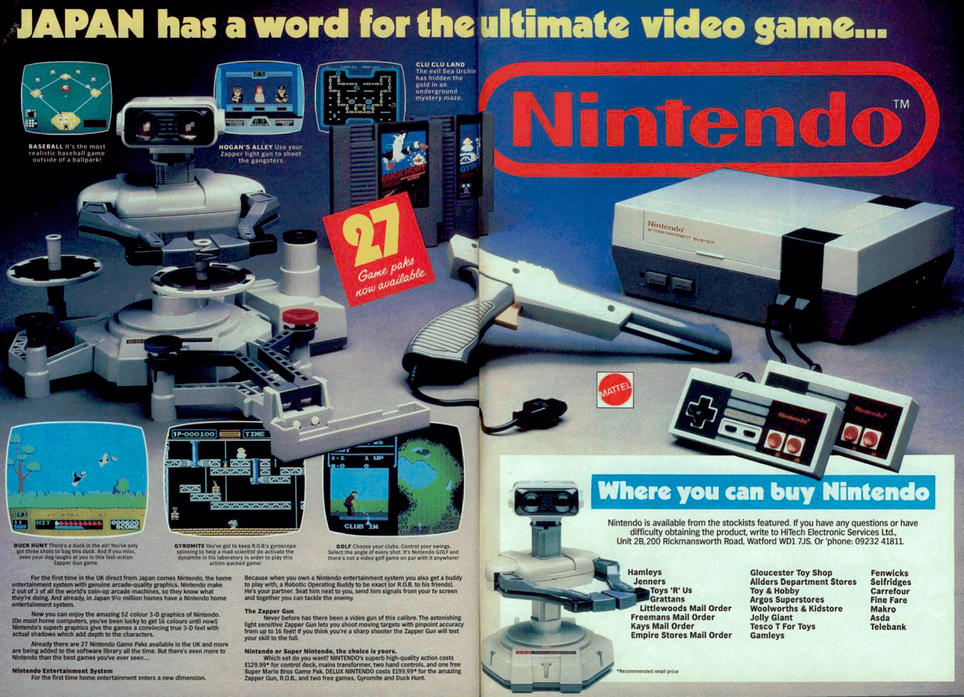

The NES case became angular, black and gray, resembling household electronics-VCRs or stereo systems. Gamepads were now connected via connectors (and not soldered to the board, as in Japan). Cartridges received a new, larger form factor-like "floppy disks of the future." With its whole appearance, the console said: "I am not a video game. I am a serious device for serious people".

Prices emphasized this message: $299.99 for a set (including joysticks and a Zapper light gun), $29.99 for a cartridge with Super Mario Bros. or similar game. At the same time, the cost of the console itself was $89.99.

Taking into account inflation, $299.99 in 1985 is equivalent to approximately $860 in 2025. That is-about 70,000 rubles at the current exchange rate. This is really a premium price, especially against the background of the Japanese 14,800 yen (~$60 in 1983). But the USA has always been an expensive market-especially in the 1980s.

However, Nintendo's main problem in the USA was not the price and not the technical characteristics. The quality of the console was high. The starting lineup of games-already included a dozen strong projects: Super Mario Bros., Duck Hunt, Kung Fu and others. Everything worked. Everything was fun.

The problem was that no one believed Nintendo.

For Americans in the mid-1980s, Nintendo was just another Japanese company that came to conquer the market. The era was tense: Japanese corporations were actively displacing American manufacturers in the automotive industry, electronics, and household appliances. The media constantly sounded alarming headlines about the "Japanese invasion." The "Japanese invasion" even penetrated into cinema: in the film "Die Hard" (1988), terrorists seize the skyscraper of the Japanese corporation Nakatomi.

Some Japanese brands managed to gain a foothold-Sony, Panasonic, Toyota. Others remained "foreign." Nintendo fell into a gray area: few people knew who they were and why they needed the American video game market.

And this market, by the way, was considered dead.

Just two years ago, in 1983, the largest crash in the history of the gaming industry occurred. In the early 80s, analysts predicted rapid growth: the home console market seemed like a gold mine. Hundreds of companies rushed into it-from giants like Mattel to garage startups. Many had neither experience nor understanding of what a game is. The result is a flood of the market with faceless, poorly made products.

The industry leader, Atari, instead of strengthening confidence, accelerated the collapse. In 1982, the company obtained the rights to the game adaptation of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial-the most anticipated film of the year. In a hurry, in six weeks, the development team created a game that would later be called the worst in history. Atari printed several million copies, expecting record sales. As a result, most of the cartridges never left the warehouses.

A little later, Atari secretly buried millions of unsold copies of E.T. in the New Mexico desert.

Against this background, the appearance of Nintendo with a new game console looked, to put it mildly, extravagant, if not crazy.

To offer Americans another game console-after the industry collapsed, stores wrote off millions of dollars in losses, and consumers lost confidence?

It looked more like an adventure than a business plan.

But Nintendo went further. She didn't just bring the console. She redefined the rules of the game. First-at the local level: in New York, where the pilot launch started in October 1985. Then-in Los Angeles. Then-in Chicago, Dallas, Seattle. Step by step, city by city.

Of all possible approaches, Nintendo chose the most unexpected: no associations with video games. After the crisis of 1983, this phrase caused retailers a reflex of disgust. Therefore, NES was not called a console. Not called a gaming system. It was presented as an "entertainment system for the whole family"-Entertainment System, not Video Game Console.

Even the appearance was part of the disguise. Gray case, angular shapes, a cartridge slot resembling a tape recorder-all this was supposed to convince the buyer: This is not a toy. This is electronics. Like a TV or VCR.

But the real genius was the tactic of penetrating into retail chains.

The console was sold not in the video game department, but next to toys and household appliances-sometimes even in the Laser Tag and electronic puzzle section.

To convince skeptical store owners, Nintendo offered a buyback guarantee: if the consoles were not sold within a certain period, the company would take them back without question. For retailers, this meant zero risk.

The kit included not only Super Mario Bros., but also the robot R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy)-a mechanical toy that "interacted" with the game Gyromite. This allowed NES to be sold as an "interactive toy of the future," not as a video game device.

All this was more like a special operation to infiltrate than a classic product launch. Nintendo was not trying to convince everyone at once. She created a loop of trust: first-one city, then-proof of demand, then-expansion. Each successful store became an example for the neighboring state.

And it worked.

By the end of 1986, NES was already sold throughout the country. By 1987, it controlled more than 60% of the market.

And this launched a powerful feedback: the more consoles-the more developers wanted to release games for NES. But Nintendo deliberately did not open the floodgates. On the contrary-she introduced a strict control system to avoid repeating the catastrophe of the early 80s.

It all started with licensing. Any studio, even such a giant as Capcom or Konami, had to sign an agreement with Nintendo and obtain permission to release games. In exchange for a license, developers gained access to special tools and technical support-but lost a significant part of the profit (up to 30-40%) and control over the production of cartridges.

A key element of the system was the 10NES chip-a "lock" built into each official console and each licensed cartridge. If the game was not approved by Nintendo, the chip blocked its launch. This not only protected against piracy, but also guaranteed that only proven projects would be on the shelves.

In addition, Nintendo introduced a rule: one publisher-no more than five games per year. This prevented market saturation and forced studios to invest in quality, not quantity.

Finally, each licensed cartridge featured a "Seal of Quality"-"Official Nintendo Seal". For the buyer, this was not just a logo-it was a sign of trust: "This game has been checked. It works. There are no bugs in it. You can play it."

This system was tough, sometimes Nintendo was even accused of monopolism-but it saved the industry from chaos. Unlike 1982, when hundreds of nameless copies of Pac-Man and Space Invaders lay on the shelves, now each game had an author, passed testing for compliance with quality standards, and Nintendo took responsibility.

Nintendo didn't just sell the console. She restored confidence-in games, in developers, in the very idea of home gaming. And it was NES that became the console that would determine the look of the gaming industry for many years to come.

Russia. 1992

It would be wrong to assume that the USSR at the turn of the 1980-1990s was completely behind the world trends in the field of video games. As already mentioned, since 1984, the country has been selling cloned versions of Nintendo Game & Watch portable devices under the brand "Electronics." In gaming halls for 15 kopecks, you could play domestic arcades-for example, "Auto Rally" (1986), "Gorodki" (1990) or "Highway" (1990), not counting numerous electromechanical machines like "Sea Battle."

For home use, 16-bit computers BK-0010 and later BK-0011 were produced since 1983, on which enthusiasts wrote simple but exciting games. Cloned IBM PC/XT-compatible machines also appeared in educational institutions and research institutes-for example, the popular "Search."

However, one thing is the availability of hardware capabilities, and quite another is the existence of a video game industry. There was no such thing in the USSR. No publishers, no distribution, no commercial model for distributing games. Individual projects were created by enthusiasts and distributed spontaneously: copied to audio cassettes or floppy disks, rewritten "from hand to hand."

Therefore, when clones of Atari 2600 and, especially, ZX Spectrum 48K/128K appeared on the shelves in the early 1990s, they caused an instant collapse of interest in domestic computers. There were simply not so many games on the BK. And Spectrum and Atari had hundreds of hits accumulated over the 1980s.

This is how a spontaneous, "underground" video game market was formed-without brands, without guarantees, without official deliveries. But with huge demand.

Large Western players in the industry-Nintendo, Sega, Atari-did not consider the CIS as a potential market at all. Probably, their headquarters believed that Russia at that time was able to consume only "Bush legs", but not expensive gaming devices. There was no infrastructure for distribution, currency restrictions made imports unpredictable, and the concept of "intellectual property" in the post-Soviet space was perceived more as a curious Western quirk.

However, the massive demand for ZX Spectrum clones suggested otherwise. In the CIS as a whole and in Russia in particular, there was a market-huge, hungry, ready for a new experience. It's just that none of the "big" ones noticed it.

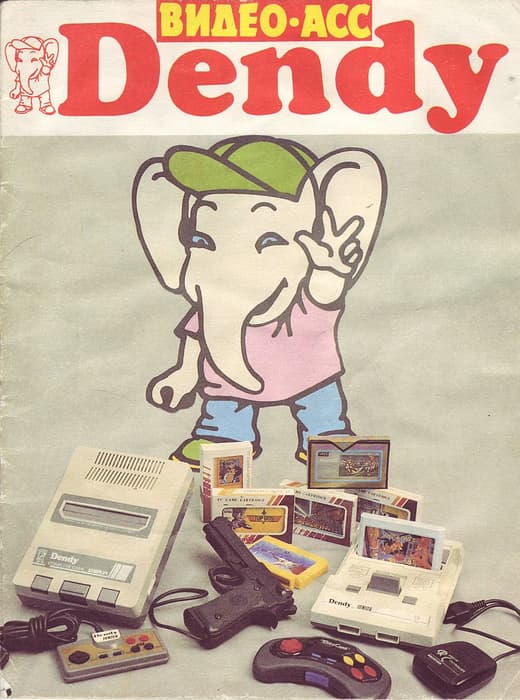

And then other players came on the scene. In 1992, an advertisement appeared on Russian television: "Dendy! Everyone is playing!"

The console with a gray case and two joysticks, similar to NES, but without the Nintendo logo, instantly became iconic. It was made qualitatively-unlike many Spectrum clones, it did not require fussing with connecting to the TV and supported the domestic SECAM television standard. In the stores where Dendy was sold, there were cartridges with games that did not need to be loaded for five minutes from a cassette. And the games themselves... There were no such games on Spectrum.

Contra, DuckTales, Battle City, Ghostbusters, Battletoads, Metal Gear, Metroid-and, of course, Nintendo hits led by Super Mario Bros.

Dendy was not an official Nintendo console. It was a Taiwanese clone (based on the Famicom architecture), the legal status of which raised questions, and mass deliveries to Russia and sales without Nintendo's consent were definitely outside the legal field. Orange boxes with cartridges were imported according to "gray" schemes and were not licensed. There was no question of localization at all. It was good when the games were in English-some schoolchildren understood it somehow. Cases when versions in Japanese came across were much more fun (and difficult)-even excellent students gave up here.

But all this did not matter. In the mid-1990s, everyone really played on Dendy.

Perhaps, in no country in the world has Famicom/NES become such a cultural phenomenon as in Russia. Correct in the comments if we are mistaken, but a television show on the central channel dedicated to a specific game console-"Dendy - A New Reality"-was, it seems, only in our country.

For millions, Dendy became the first real game console. For many-the most iconic to this day. And for Nintendo-the strangest triumph: its product conquered a country where it did not even try to work. The company, which built its empire on total control, unwittingly spawned a cultural phenomenon in a country that it officially ignored.

Analysis

The history of Nintendo is not just the history of a successful product. This is the story of how vision and perseverance can rebuild reality, creating an industry from the wreckage of a crisis. NES proved that technologies do not have to be the most advanced for a breakthrough-they must be offered to a world that is not ready for them, but in which demand is already ripening.

The irony is that after 40 years we see a full circle. Today's global and instant gaming market is the realization of the very dream of accessibility that Nintendo once realized, albeit in fragmented markets. And the incredible popularity of "Dendy" in Russia became a lesson: real cultural expansion sometimes occurs against the will of the company itself. A product created with Japanese scrupulousness and brought to the market with American pragmatism found its most loyal and nostalgic audience where it was never officially sold.