There are games that even the most confident developers are afraid to touch when it comes to remakes-they are so complete, refined, and self-sufficient that any intervention risks distorting the author's intent and disrupting the internal harmony. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is one of those. Twenty years ago, Hideo Kojima released a work that rightfully earned the title of masterpiece and a place in the pantheon of video game classics. Paradoxically, it is perhaps his most straightforward and accessible work-making it the best way to get acquainted with the Metal Gear series and the work of Hideo Kojima in general.

A Virtuoso Mission

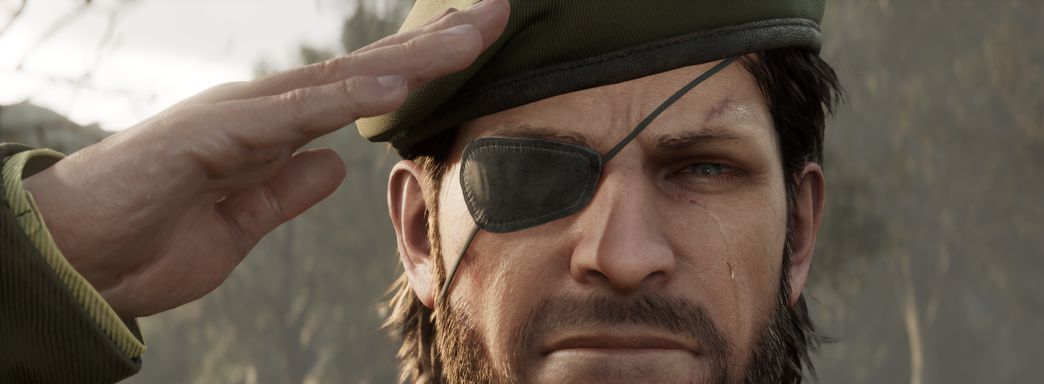

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater holds a special place in the series' chronology. It is the fifth installment in the series, the third in the Metal Gear Solid line, and the starting point of the entire saga. It tells the story of Naked Snake, who is destined to become Big Boss-the founder of FOXHOUND and a central figure in the universe.

The action takes place in 1964, at the height of the Cold War. A CIA agent codenamed Naked Snake is sent to Tselinoyarsk, a fictional region of the Soviet Union, to retrieve scientist Nikolai Sokolov, who is busy creating an experimental weapon capable of changing the balance of power in the world.

GRU Colonel Yevgeny Volgin interferes in the operation, driven by his own ambitions-and everything goes to hell. But for Snake, the heaviest blow is the betrayal of his mentor, the legendary Boss. She defects to the enemy, attacks Snake, and leaves him to die. Soon after, the American portable nuclear warhead she handed over to Volgin turns a Soviet base into ruins, provoking an international crisis.

And that's just the prologue. All these events unfold literally in the first hour of the game. A week later, Snake must return to Tselinoyarsk with a new mission codenamed "Snake Eater" to stop Volgin, deal with the Boss, destroy the "Shagohod"-Sokolov's combat vehicle-and prevent World War III.

At first glance, we have a classic spy thriller with a secret operation behind enemy lines, a hunt for a doomsday weapon, and a confrontation between student and teacher. But in the hands of Hideo Kojima, familiar clichés take on new meaning. He deliberately uses hackneyed constructions to then dismantle them, ridicule them, rethink them, and turn them into a tool of expression.

Behind the facade of a story about spies during the Cold War lies something much bigger-reflections on the role of the soldier as a political tool, on the price of duty and patriotism, on the spiral of violence that reproduces itself. About where to look for truth in the post-truth era, where all participants are just actors on the world stage, and their roles change as rapidly as the wind drives dry leaves.

Politicians come and go. Enemies become allies, allies become enemies. It all depends on the script. Fates are ground in these millstones, names are erased, meanings are distorted. It is not surprising that these themes resonate today no less sharply than twenty years ago. It is enough to take a quick look at the news feed to be convinced-Kojima is still a visionary, capable of using artistic images and hyperreality, this exquisite mixture of fiction and history, to comprehend not only the past, but also the present and the future.

Those who are only familiar with Kojima's work through Death Stranding may easily be mistaken in thinking that everything is once again wrapped in metaphysics, pseudoscience, and a kaleidoscope of philosophical allusions. But here, everything is arranged differently.

I do not agree with the simplified formulation "Death Stranding is a pretentious Japanese nonsense." This is usually said by those who are afraid to look under the rug of a work of art and expect from the game only entertainment without unnecessary semantic load.

But if we resort to such definitions, Metal Gear Solid 3 is that very vigorous and mischievous Japanese nonsense. We can say that form triumphs over content here (although only at first glance) and at the same time serves entertainment-it clouds the eye with inventive battles with bosses who have supernatural abilities, dizzying cinematic scenes, pathos, absurdity, and an abundance of slow-mo.

Even a falling cigar gets its minute of fame in three angles, and no one asks why young Ocelot meows, calling for fighters. It's absurd and surreal, and that's why it's incredibly exciting. And it's not worth approaching such moments with a measure of logic.

In addition, Kojima ridicules the Americans' obsession with weapons, bringing it to the point of grotesque. He plays with the theme of objectification of women, allowing the player to enjoy the charms of Eve, flirting with the serpent-tempter in the person of the protagonist, and at the same time creates one of the most tragic and strong female images in the history of games-the image of the Boss.

And while you sincerely enjoy the chaos of what is happening, lose vigilance and immerse yourself in the performance, Kojima is just waiting for the moment to pull the player up short in the final and strike at the most painful. This adventure in the Soviet jungle stays with you for a long time, and it is difficult to hold back tears when the screen is filled with credits under the piercing Way to Fall performed by the British Starsailor.

Unlike Death Stranding, most of the plot lines and meanings here lie on the surface, and the ending gives answers to the main questions-even if you do not strive to dig deep. Of course, Kojima remains extremely self-referential and generously scatters references to his own work and world culture, not restraining himself in this impulse. Therefore, some details may slip away, especially if Delta becomes your first acquaintance with the series. But in 2025, there is simply no better entry point into Metal Gear. Moreover, we have one of the benchmark stealth-action games, which has practically no analogues in the modern industry.

Stealth in the Grass Before It Was Famous

At the heart of the gameplay lies a seemingly familiar formula-to secretly advance through enemy territory, eliminate those who get in the way, or bypass them, distracting them, just to complete the task. But the main charm of MGS3 is that it is not at all the "stealth in the grass" that we are used to in modern games.

It is not recommended to leave traces of your presence, so our "snake"-Naked-starts almost naked, with a minimum of equipment. Snake will have to get everything else right in the field-weapons, equipment, and useful gadgets.

Snake Eater for the first time takes the usual formula of the series beyond military bases and secret laboratories-into dense jungles, forests, and mountains, where full-fledged elements of survival appear. Camouflage requires you to choose a uniform and face paint to match the color of the environment, and sometimes this allows you to literally merge with the background, hide in plain sight of enemies, and even deceive bosses.

In addition, when special conditions are met, camouflages with unique effects are opened-from muffling steps to absolute disguise. Delta has added a quick change of disguise in a couple of clicks, although you still have to refer to the "survival menu," although not as often as in the original.

Gunshot wounds, burns, fractures, and poisoning do not pass for Snake without a trace, they must be treated in a timely manner. A stuck bullet will have to be dug out with a knife, the wound disinfected, the bleeding stopped and bandaged, and if it is torn-also stitched. In 2004, this approach looked fresh, but today it is perceived more as a relic of the past and an excessive tribute to realism.

Still, all manipulations are performed in a separate menu and always according to the same scheme-this knocks down the pace, especially during battles with bosses. But scars and traces of wounds remain with the hero until the very end: his body gradually turns into a living diary, on which the entire path traveled is imprinted.

Snake is also forced to maintain a supply of strength by eating found food or wild animals. Energy affects the restoration of health, the ability to hold your breath underwater, climb ledges, and even hold weapons in your hands. In addition, a hungry "snake" is able to give out its location with a treacherous rumbling of the stomach.

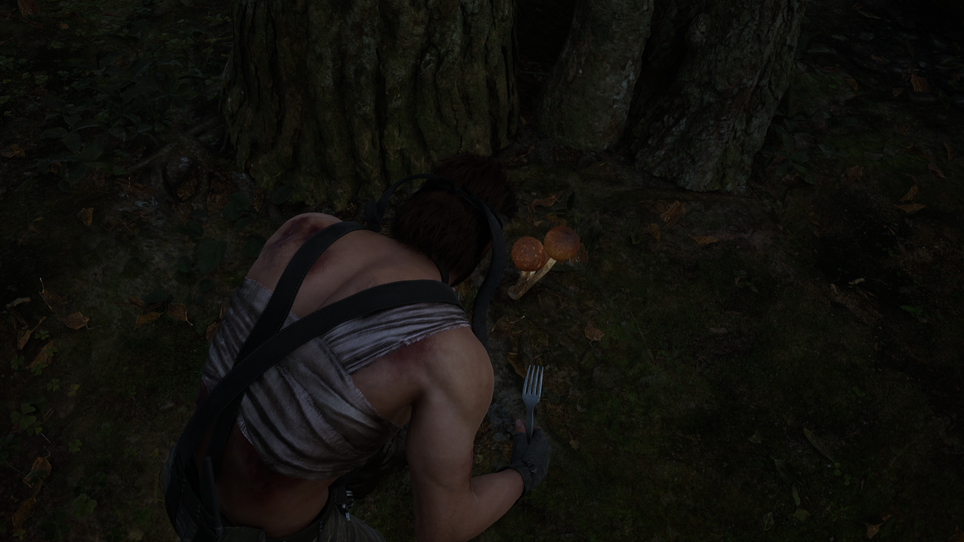

Nevertheless, this mechanic should not be overestimated-it almost does not complicate life and only adds a pinch of realism. Decent food almost always runs or crawls somewhere nearby. In the end, chewing on a rat or chasing mushrooms with a knife in hand is far from the worst test on the way to saving the world.

Another thing is when hunting becomes part of a creative approach to passing. Sometimes you can feed the guards expired supplies, and then they will rush to look for a toilet, leaving the post unattended. Or you can throw a poisonous snake at them to distract them.

By the way, you can throw not only food or animals at enemies, but also magazines of dubious content. However, "creativity" is perhaps the main word that should be kept in mind when starting the game.

Even battles with bosses here are not like each other and can be passed in non-standard ways. I will not go into details-in case you have not played yet-although most, I think, have heard about many of them.

One of the bosses can be eliminated even before a personal meeting-it is enough to shoot in advance, or even wait for his death from old age, simply turning off the game for a week or moving the system clock.

Another can be poisoned with spoiled food or thrown a poisonous mushroom at him to tip the scales in his favor. The third can be outwitted by trying on someone else's mask or scaring him with a frog.

And somewhere you can even die on purpose, so that then, using a resurrection pill, strike on the sly or skip the fight altogether.

Each location and each duel here is perceived as a puzzle with several ways to solve it. Snake has a whole arsenal at his disposal-motion sensors, microphones, sleeping cigarettes and, of course, the legendary cardboard box, which unexpectedly turns out to be useful even against the fire of one of the bosses. You can deal with opponents in different ways: eliminate, stun, put to sleep or, using CQC close combat techniques, take prisoner, interrogate and even use as a human shield.

Snake Eater encourages ingenuity and gives a truly flexible stealth-action. It is worth playing here carefully: communicate with characters on the radio to get new information, look for non-standard ways to deal with enemies, or just hear memories of cinema, which Kojima puts into the mouth of the Paramedic. But in order for the game to unfold in all its fullness, it is also important to choose the right level of difficulty.

Two game styles are available in Delta-"Original" and "New." The first reproduces the classic fixed camera of the 2004 model, while the second offers a modern third-person view, allowing you to move and aim at the same time, including first-person aiming. This approach noticeably facilitates control, but at the same time reduces the level of challenge. The developers tried to balance this by adding full-fledged ballistics to sleeping darts, so it will no longer be possible to distribute headshots at any distance.

It is better for beginners to immediately choose a high difficulty instead of the usual "medium." Even the standard mode feels like an easy walk, while "extreme" turns into a full-fledged test without the right to make a mistake-especially in duels with bosses. This level is more suitable for those who remember the original well and know all its "features."

I would not recommend light modes at all: with them, the game is easy to "break," depriving it of the main pleasure. Of course, everyone is free to play as they like, but it is the high difficulty that makes you use the entire available arsenal and keeps you from the temptation to turn into Rambo, mowing down enemies without hesitation.

MGS3 is revealed in full precisely in a stealth passage at a decent level, where discipline and ingenuity are valued much higher than brute force. Personally, I played the game on "extreme," and I can't bring myself to call the enemies blind, deaf, or primitive-the game really tested me. In the final, I felt a whole range of feelings: sadness, melancholy, satisfaction from the work done, and a slight fatigue from how difficult my path turned out to be.

Old Snake in New Skin

Delta cannot be called a full-fledged remake in the usual sense. Many are more likely to consider it a remaster or a graphic re-release, because Konami and Virtuos did not rewrite the classics, but only updated its appearance and allowed the old snake to shed its skin.

The architecture and logic of the levels have remained unchanged, so the player again finds himself in compact zones-"rooms" with patrols, separated by black loading screens. Even in Grozny Grad, where you can see the continuation of the location through the fence, you can only get there through the loading screen. It is not surprising that the game still evokes strong associations with a series of stealth puzzles.

The transfer to Unreal Engine 5 has turned the jungles of Tselinoyarsk into a dense and almost tangible landscape. Detailed foliage, soft lighting, and atmospheric effects make familiar scenes more vivid and at the same time emphasize the contrast between the realistic environment and the grotesque absurdity of what is happening, allowing Kojima's voice to sound even brighter.

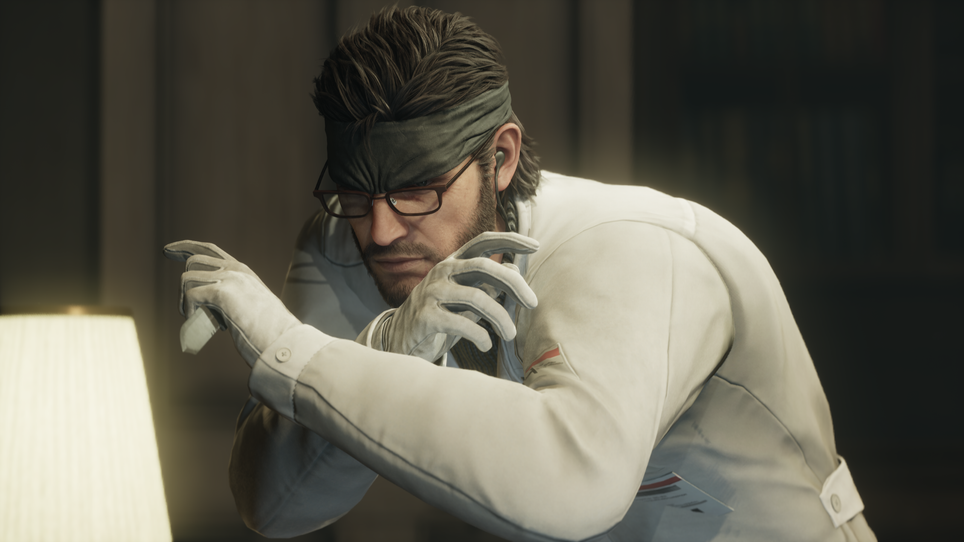

Everything is more complicated with the characters. They have become more expressive and detailed, the faces look more elaborate, and the equipment flaunts fasteners, buckles, and elaborate fabric textures. But at the same time, part of the signature charm and cartoonish caricature has gone. Now the heroes get wet in the rain, and dirt immediately sticks to Snake's clothes and face. He himself moves more naturally and has gained weight-it will no longer be possible to spin like a top on the spot, and he has become noticeably less agile on the ground.

New animations have appeared in close combat, depending on the position of Snake and the enemy, whereas before there was only one. But the physics of Eve's breasts has sunk into oblivion, and the faces of some characters in certain angles involuntarily resemble the effect of a sinister valley. Nevertheless, emotions are now read much better, and the Boss's gaze, full of bitterness, hits much harder, hitting the very heart.

Visually, Delta is impressive, but Virtuos has again failed with optimization. Even on RTX 4070 Super in native 1440p, the game holds only 45-50 frames, and stable 60 can only be obtained with DLSS in "quality" mode. Such performance looks unacceptable, because with all the work on graphics, it is difficult to call the project a full-fledged representative of the current generation.

And yet, with all the compromises, Delta copes with the main thing-it gives you the opportunity to relive the cult story in a guise that is more in line with modern standards. Konami has finally assembled the "complete" edition of Metal Gear Solid 3, combining disparate elements from different versions for many platforms-from additional settings to rare bonus content. All this, combined with creative gameplay, encourages repeated playthroughs and allows you to get the most complete gaming experience.

The mini-game with catching monkeys, the hidden cinema, and the slasher Guy Savage, created with the participation of Platinum Games, which is just asking to become a separate game, have returned. A little later, the Fox Hunt mode should appear, which will add cooperative entertainment to this set, and this sounds especially promising against the background of the lack of worthy analogues and the cancellation of the online The Last of Us.

Yes, if you want, you can scold Virtuos for the small number of changes and shout F*** Konami for the exorbitant price tag in some regions, especially since the MGS 3 version from the Master Collection can be bought much cheaper and get almost the same experience. But Metal Gear Solid 3 has always been a piece, an author's work, and it remains so. Before criticizing the remake in this vein, it is worth asking the question: who in the gaming industry is capable of taking on a remake of Hideo Kojima's game and reassembling it from scratch so that it remains Hideo Kojima's game?

There are games that even the most experienced and self-confident developers are afraid to touch when it comes to remakes. They are too complete, verified, and self-sufficient, and any intervention threatens to distort the author's intention and disrupt the internal harmony. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is one of those. That's why we love it.

Diagnosis

Metal Gear Solid Delta: Snake Eater returns us not to the origins of the stealth genre, but to one of its peaks-and does so with respect and caution. Yes, the remake can be called lazy: the scale of changes is incomparable to what we saw in the updated Resident Evil 4 or Silent Hill 2. But it is precisely because Delta retains the formula and spirit of the original that it works as strongly as twenty years ago. Everything is in its place here-deep stealth mechanics, the tragedy of Snake and the Boss, absurd humor, and cinematic quality.

In a sense, the situation with MGS3 is reminiscent of Death Stranding. Even if the plot and the ideas embedded in it leave you indifferent, you will still have a magnificent stealth-action game with rare variability and a rich arsenal. And if you allow yourself to share Kojima's pathos and madness, you will have a unique experience and an adventure that simply has no analogues in the modern industry.

Yes, technical limitations, controversial optimization, and an inflated price tag in some regions can scare away some players. But it's still a masterpiece-but, as before, not for everyone. Delta gives you the opportunity to relive key moments in the history of the series and take a fresh look at its legacy. For fans of Metal Gear and Kojima, this is a real gift, and for beginners-one of the best entry points into the work of the "genius."

![[Video] Thanks, Huang! Steam Decks, CPUs, DDR, HDDs, SSDs Are Out of Stock / UE5 Problem for PS6](https://media.ixbt.site/312x192/smart/ixbt-data/1125040/01KJ5KX5TFGK673B2J2HDF9BJH.jpg)

![[Video] The California Bubble / How Toxic Positivity Destroyed the Gaming Industry](https://media.ixbt.site/312x192/smart/ixbt-data/1125026/01KJ5FHXQMWCM616ZE3W78Q8H2.webp)