The ARC Riders PR campaign created the image of an allegedly benevolent game where players don't fight each other, but explore the world and interact together. The network was filled with videos and reviews talking about "friendly raids" and "an alternative to Tarkov without pain and loss." But the reality turned out to be much scarier.

Arc Raiders appeared in the information field long before its release. From the moment of the first trailer, the project was positioned as "a new word in the extraction shooter genre." The media and blogs talked about "a new approach to cooperation," about "humane PvP," about "an ecosystem of trust between players." Behind these formulations was an attempt to make survival friendly and the genre mainstream.

At the level of ideas, this looked promising. The developers at Embark Studios had already proven that they can make visually expressive and technologically advanced games - The Finals has become one of the most spectacular online shooters in recent years. But Arc Raiders turned out to be a product of a different type: ambitious in form and empty in essence. Behind the possibility of cooperation lies a system where almost every element works against the authors' intentions. On the other hand, these mechanics were able to attract the attention of 400,000 people, which allowed the game to reach the Top 1 in sales for a couple of days and displace Battlefield 6.

In theory, casualization sounds like a logical step: lower the entry threshold, remove annoying elements, and make the genre less toxic. In practice, only the shell remains of the genre core - raids, evacuations, empty tasks, battles with bots and players for valuable loot.

Machine Rebellion Without Nuclear Ash

ARC Raiders has a plot that feels like a formality. Once every few missions, the player receives short cutscenes that are supposed to advance the narrative and reveal the context of the Second War with the Machines. According to Embark Studios, humanity survived the First War, retreated underground, and is now preparing for a rematch. We play as a raider - a fighter, scout, and resource gatherer for the Resistance.

The problem is that these plot inserts explain almost nothing. They create the impression of movement, but do not give an understanding of where exactly the action takes place, who the key characters are, and how the events are related to each other. The cutscenes look like fragments of a larger plot that was never realized. They do not form either motivation or emotional attachment.

The only place where you can get at least a partial idea of the world is the codex. It contains fragments of lore, records of opponents, descriptions of technologies, and records of completed tasks. The codex functions as an encyclopedia - useful, but dead. It tells, but does not show. Reading replaces action, and information remains isolated from the gameplay.

Because of this, the plot looks like a background decoration, existing parallel to the game. We seem to be participating in the Second War, but we do not feel its scale or its purpose. The developers technically support the "post-apocalyptic survival" genre, but emotionally the game does not involve you in its world. Even in the Tarkov beta test, the plot feels much more complete and elaborate than here. And this is despite the fact that ARC Raiders was originally conceived as a PvE adventure, which is manifested in all other game mechanics.

Maps and Raid Structure

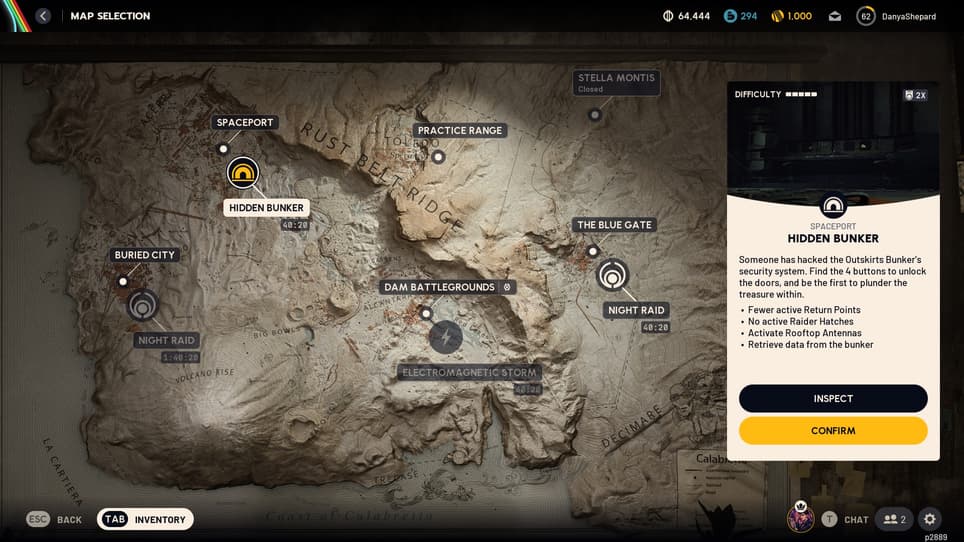

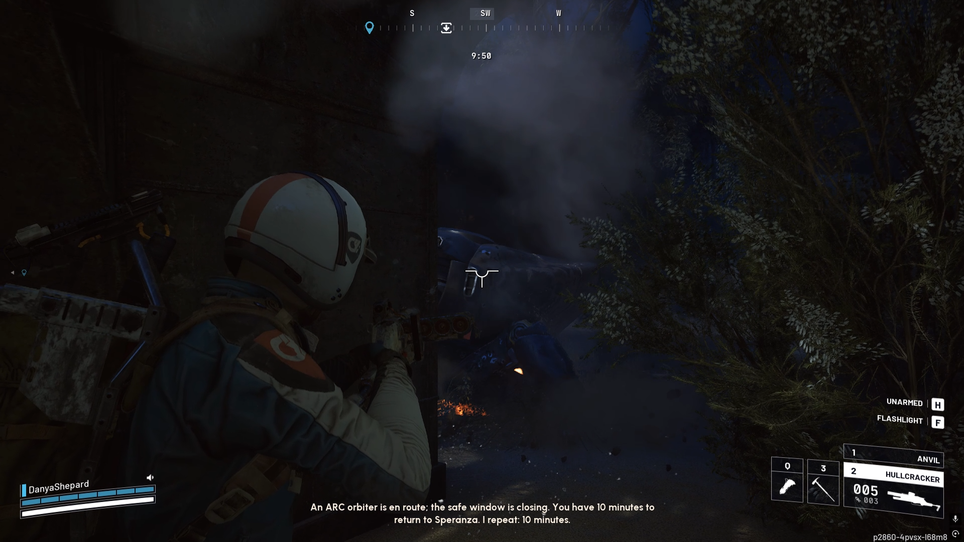

Currently, there are four active maps in the game, and one is planned by the end of November. Each is a separate biome with its own geometry, lighting, and risks. The Dam and the Buried City concentrate players looking for a quick shootout. The Cosmodrome is built around large robots that are profitable to farm for rare components. Blue Gate is a spacious wasteland without cover, where you feel vulnerable every second.

ARC Raiders boasts a detailed setting among modern extraction shooters. The game features several large regions, and they are all built on the principle of contrasts. Some maps are dominated by open plains, where it is important to use cover from stones and folds of the terrain, while others have mountainous elevations and industrial zones, providing the possibility for sniper fire. In other places, you can find dense forests that can cover you from unnecessary attention from drones and other players.

But the main advantage of the maps remains their internal saturation. In addition to natural shelters, many buildings are scattered around the locations - residential buildings, hangars, warehouses, research stations, and destroyed communications. These points of interest serve as sources of resources. In houses, you can find household appliances and jewelry. In industrial zones - materials for crafting and blueprints, and at guard posts - weapons, ammunition, and shields.

As in Escape from Tarkov, there are rooms here that require special keys to access. This creates additional motivation for exploration and the risk of collision with other players hunting for the same trophy. However, Embark approached the access system creatively: some doors are opened not with a key, but with the help of mini-games to search for batteries or buttons that are hidden around the location. And for others, a special skill is required, which is unlocked in the skill tree.

However, large spaces also have a downside. On such maps, it is easy to get ambushed: the enemy can take a height or a bush and open fire first. As in other extraction shooters, the advantage is often gained not by the one who shoots better, but by the one who noticed first. This is not a flaw of a particular game, but a feature of the genre. ARC Raiders is no exception here.

In addition to the maps, we choose the proposed modifiers, which are shuffled every few hours. Sometimes these are simple bonuses to the drop of certain resources, sometimes serious challenges such as an electromagnetic storm or night raids, where only a couple of exits will work. There are also special missions: raids into a secret bunker, from where you can take valuable data, or a raid on the Queen, who guards a capsule with legendary blueprints. These events completely transform the game from a regular extraction shooter into something like Hunt: Showdown, where all raid participants either go to complete the key task of the event, or wait for others to do everything for them.

Even Here There's Nothing to Wear

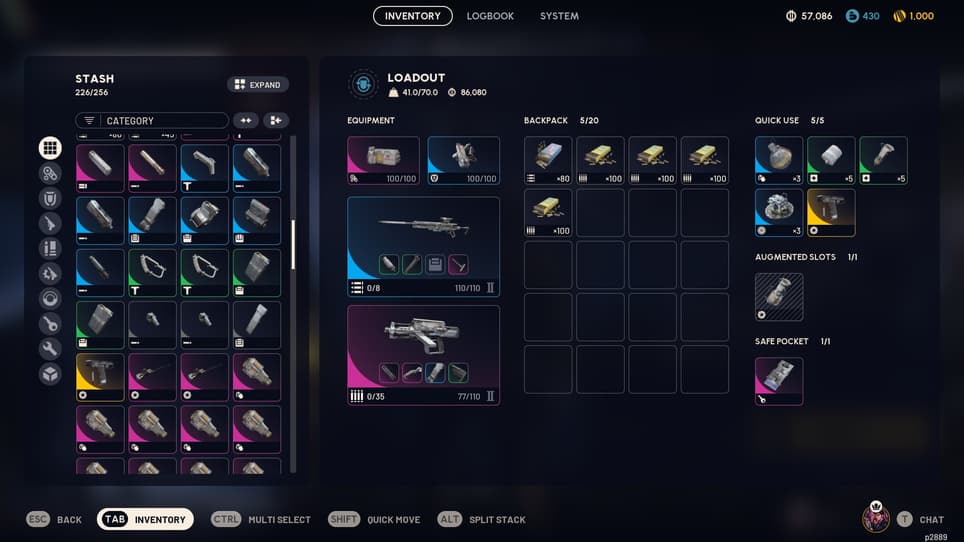

As in any other representative of the extraction shooter genre, the success of a raid in ARC Raiders begins not with the first shootout, but with preparation. The selection of equipment determines not only the chance of survival, but also the style in which you will act during the mission. The game does not overload the interface with details, but the equipment system here is so flexible that each player can find their own balance between mobility, protection, and utility.

The basic set of equipment includes an energy shield, two slots for weapons, several slots for consumables, and an augmentation - a key element that determines the style of your raider. It is the augmentation that sets the structure of the inventory and compatibility with shields.

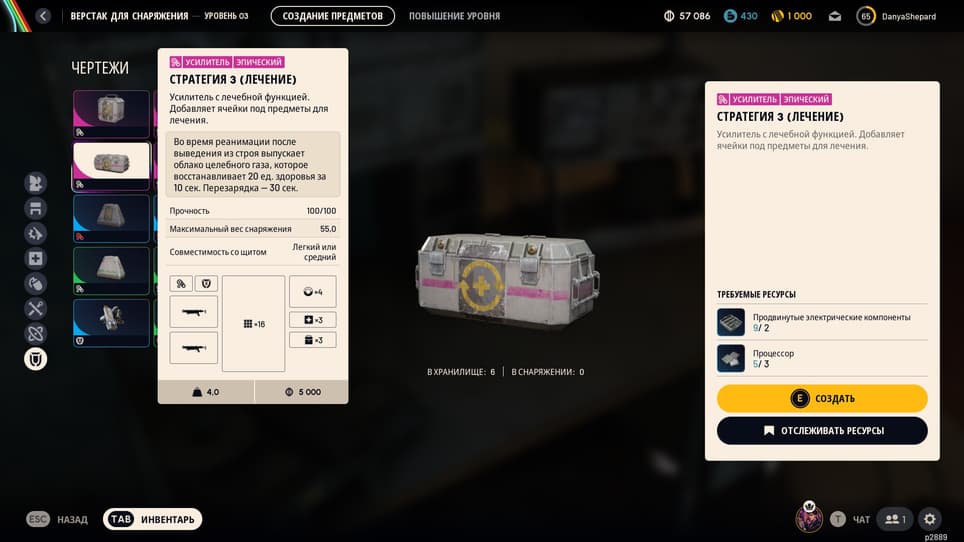

There are several types of augmentations: combat, assembly, and tactical. Combat augmentations increase survivability in battle. For example, the cheapest combat module allows you to wear a medium shield. Assembly augmentations are aimed at loot and logistics - they give more slots for loot, greater carrying capacity, but are only compatible with light energy shields. Tactical modules enhance interaction with allies and add auxiliary abilities. More advanced augmentations introduce unique effects. For example, the "Defense" module provides the player with an endless battery to recharge the shield, and the "Medic" module creates a healing cloud if its owner has revived an ally.

The player's defense system is much simpler. There are only three levels of protection - light, medium, and heavy. They differ only in the number of health units and the percentage of damage absorbed. The damage mechanic resembles the model from Counter-Strike: the shield takes part of the damage, gradually losing strength. After destruction, all incoming damage begins to go directly to health. The difference between the levels of protection is felt minimally - the advantage is given not by the characteristics, but by the ability to competently take cover, keep your distance, and hit the head. Therefore, the owner of the strongest shield does not have a decisive advantage in a duel.

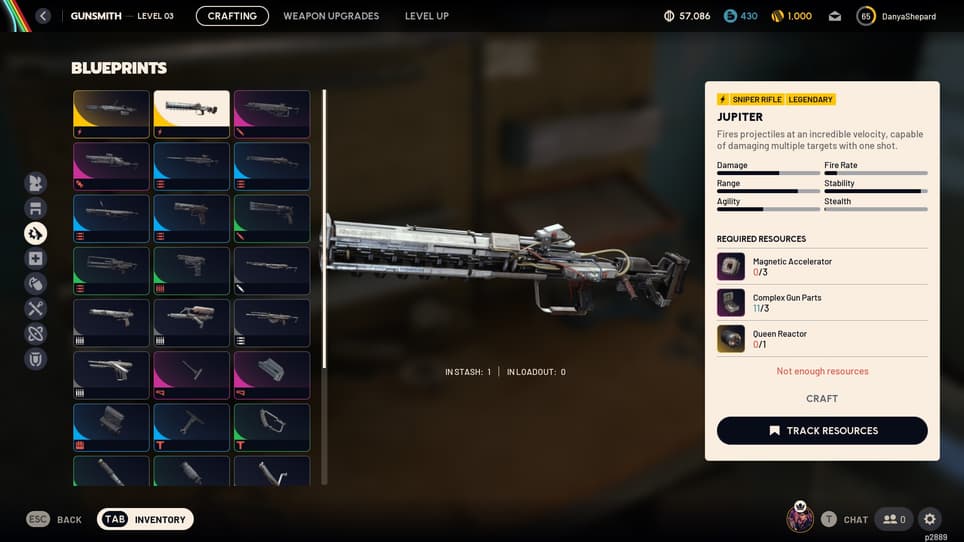

The weapon system is much more thought out. The game features 20 weapons, differing in calibers, damage, and rate of fire. The arsenal covers almost the entire usual range: from standard pistols and shotguns to legendary energy rifles and machine guns. Each type of weapon has its own purpose, but its effectiveness depends on who you are fighting against.

The division of weapons into PvE and PvP directions creates an interesting, but controversial balance. For example, a single-shot rifle is ideal for destroying robots and sniper fire, but almost useless up close. At the same time, a regular submachine gun with a high rate of fire allows you to easily neutralize another raider, even if he is equipped with legendary weapons. The effectiveness of weapons is determined not by its rarity, but by the context of use and personal skill in wielding it.

The situation is even more complicated with heavy weapons. Grenade launchers and cluster grenades - the only examples of heavy artillery - are effective exclusively against machines. The explosive device detonates only when it comes into contact with mechanical targets. If you use it against people, there will be no detonation.

Shooting is Worse Than in Tarkov

ARC Raiders is based on simple arcade rules. The developers abandoned the detailed model of damage to limbs, bleeding, and injury statuses, leaving a two-level system: an energy shield and a health bar. Unlike Tarkov, where shooting at the legs is a special tactic, here the damage is perceived in a generalized way. This makes the game more accessible, but removes the scope for tactics.

The main problem lies in the TTK - the time it takes to kill an enemy. In ARC Raiders, it is significantly higher than in most analogues. Even with accurate shooting, a player can put half a magazine into an opponent before he dies. As a result, each shootout turns into a protracted exchange of shots, where the winner is not the one who shoots more accurately, but the one who is better prepared and has a faster reaction speed.

This system directly affects the perception of PvP. It is impossible to eliminate an opponent with one shot in the game - even if you hit the head. Bullets are divided into several types of caliber: light, medium, heavy. But the damage depends not on the ammunition, but on the specific weapon. As a result, a sniper rifle and a machine gun using the same type of cartridge inflict damage that differs by orders of magnitude. This convention makes the battle less readable and more laborious: one opponent may require either 2 successful headshots from a revolver, or a whole magazine from a cheap pistol.

At the same time, this system feels more natural in PvE mode. Enemy robots are divided by type, size, and resistance to damage. Small drones are destroyed quickly, and large mechanisms require tactics to inflict damage on vulnerable areas. And some feel like mini-bosses, forcing you to change position and use grenades. It is in such battles that the entire combat potential is revealed: a long TTK is justified because the enemy is massive, and the destruction process is multi-stage.

But TTK is only part of the problem. The real trouble lies in the technical part of the game, related to the tick rate - the frequency with which the server updates information about the positions, actions, and state of players: the higher the tick rate, the faster the game responds to the user's actions. For multiplayer shooters, a high frequency is critical, since the correctness of hit registration and the smoothness of shootouts directly depend on it.

In ARC Raiders, the tick rate of servers is limited to 30 Hz, which is noticeably lower than the standards of the genre. For comparison, in Battlefield 6, the update frequency is 60 Hz, and on FaceIt servers in Counter-Strike 2, it was 128 Hz up to a certain point. But since the release, Embark servers have not been able to cope with such a load and lose up to 90% of all data packets, due to which the tick rate is only 3-4 Hz. This leads to characteristic problems - shots through cover, delays in damage registration, opponents continuing to move after death. And sometimes the defeated player even manages to crawl to the exit before the server confirms his defeat.

In aggregate, a high TTK and a low tick rate create an extremely unstable combat environment. Many duels between equal players end by chance: one can shoot first, but lose due to network lag; the other - survive simply because the server did not have time to record the damage received. In such conditions, the meaning of fair duels disappears. The only truly effective tactic in PvP is a sneak attack. An unexpected attack from the flank or from an ambush allows you to minimize the risk of packet loss and implement TTK before the enemy has time to react. This makes the game dependent not on shooting skills, but on stealth and positional advantage.

The Market Doesn't Decide Here

The economic model of ARC Raiders is built not on trade and currency, but on extraction. Money is a secondary element. The main source of development is loot taken from raids. It is the resources from the surface that determine how quickly you can improve your shelter, equipment, and augmentations.

Each raid in the game is not just a sortie for loot, but part of a production cycle. All found items have a direct applied meaning. Batteries are used to create shock mines and energy traps, processors are used to assemble advanced augmentations, and robot microcircuits become a key component in the production of medium and heavy shields. At the same time, "epic" resources here seem useless. They are only needed to create a couple of legendary guns and nothing more.

The role of money in this ecosystem is minimal. They are only needed to buy basic goods from merchants, whose assortment remains unchanged. As standard medicines, ammunition, and entry-level weapons were sold at the beginning of the game, so they will be sold until the final stages of progress. Shops do not offer rare items, so the trading system performs only a service function - purchasing basic consumables before the raid. The only thing for which it is really worth accumulating large sums is the expansion of the stash. It has nine levels, each of which increases the capacity of the storage, but this process is finite. After reaching the ninth level, the economy loses the meaning of accumulation.

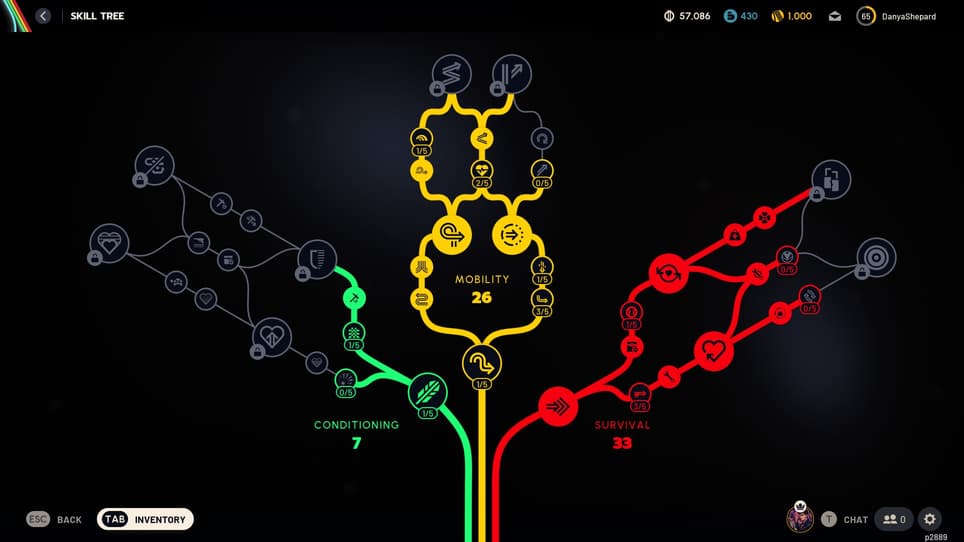

Character progression is implemented through a system of levels and a skill tree. After each raid, the player receives experience, which increases the level and gives points for distribution across three branches of development. Each branch is marked with a color and is responsible for certain game directions:

- Green branch - combat skills, weapon proficiency, and interaction with objects.

- Yellow branch - parkour, endurance, and movement speed.

- Red branch - stealth, loot detection, and resource gathering efficiency.

In practice, the balance between these directions is not verified. The skills of the yellow branch look useful on paper, but their influence is weakly felt directly in raids. Many bonuses, such as accelerated stamina recovery or increased jump distance, do not give a tangible advantage. At the same time, the skills of the green branch, related to combat mechanics, are more significant, but are often ignored by players striving for mobility.

The main nuance of the tree lies in the fact that the game does not show numerical values of improvements. The player does not see how much a certain indicator increases. This makes the system as opaque as possible: some skills are perceived as useful only at the level of description.

A serious problem of progression is the strict level restriction. The maximum level is 75, after which the character stops receiving experience and skill points. There is no way to redistribute skills: any wrong decision at the early stages is fixed forever. The situation can only be corrected by completely resetting the account in order to gain the Prestige level.

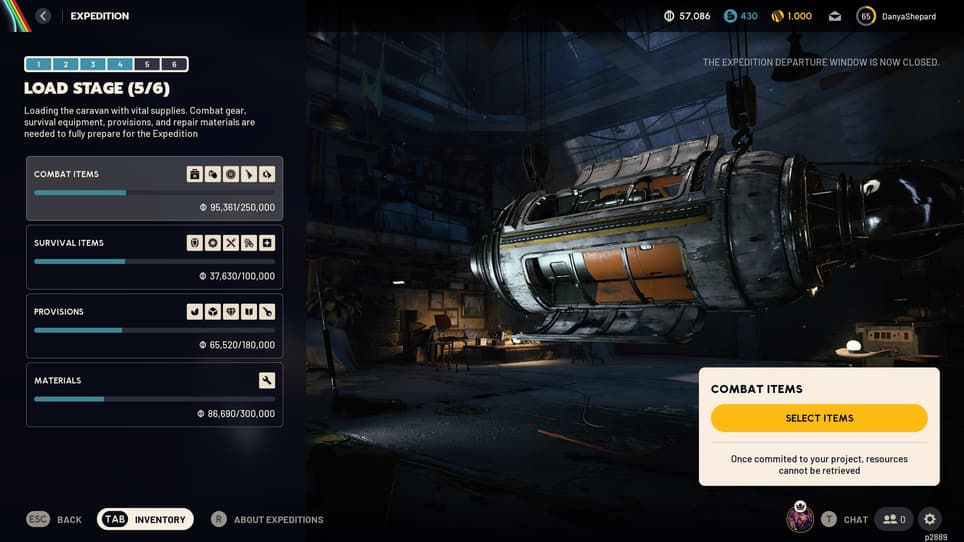

The transition to Prestige is designed as an in-game event that occurs once every 2 months. For this, the player needs to build an ark capsule, which serves as a transport for the expedition and symbolically sends your character on a new journey. And another raider comes to his place - with a zeroed level, but with bonuses to subsequent leveling and an increased inventory. The reset requires resources, so Prestige is not just a cosmetic function, but part of the overall development cycle. However, if the player does not have time to prepare the ark within the specified time, he is forced to wait for the next window to restart.

All the Beauty of Unreal Engine 5

ARC Raiders is a rare example of a game in which the visual part does not just serve as a decoration, but becomes a full-fledged element of perception. The developers from Embark Studios managed to create a holistic image of the world, where graphics, light, sound, and physics work together, forming a single sense of space. At the level of technical execution, the game certainly stands out among modern online shooters.

The basis of the visual component is a completely redesigned Unreal Engine 5. Instead of Lumen lighting, the developers integrated the much less costly NVIDIA RTXGI technology, which provides realistic global lighting: sunlight seeps through dust and fog, softly reflects off metal surfaces, and creates a characteristic diffused light in the twilight. Unlike many projects where lighting performs a purely decorative function, here it affects tactics. You can hide in the shadows even in open terrain, and bright lighting interferes with visibility from doorways.

Animations are one of the strongest aspects of the project. The movements of the characters look not just smooth, but truly lively and cinematic. Each action - whether it's a roll, jump, slide down a slope, or grab onto a crossbar - is accompanied by precise, almost physical plasticity. It is clear that this is the result of a great work of motion capture specialists: the hero's body reacts to the landscape with realistic inertia, groups together when landing, and shifts the center of gravity in various circumstances.

These elements not only add expressiveness, but also affect tactical behavior. Thanks to well-thought-out parkour, the player can use terrain irregularities, roofs, and balconies, creating temporary positions for attack or retreat. Some locations are actually built around the idea of verticality: here you can shoot from the upper floors, cling to ropes, or use a grappling hook to maneuver through the roofs.

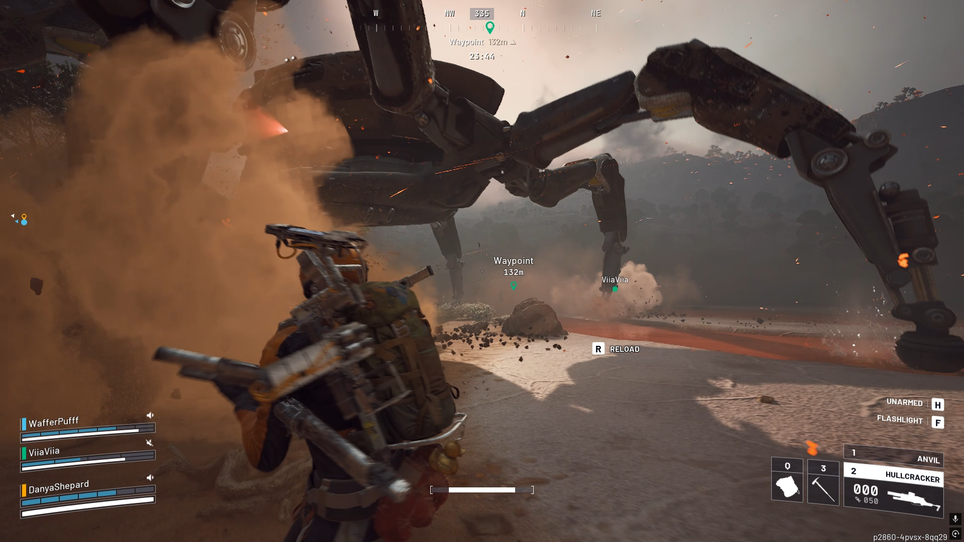

A similar sensitivity is present in robots. Almost every bot has its own set of animations in case of penetration of critical limbs. Flying drones can have their propellers knocked out, depriving them of the ability to maneuver and forcing them to fall to the ground. Large mechanical spiders are harmed by the destruction of limbs: a shot in the joint disables the leg, changing the enemy's behavior and reducing its mobility.

From a technical point of view, ARC Raiders demonstrates a rare level of optimization for a project of this scale. Even in loaded scenes, performance remains stable. This is especially important for the multiplayer format, where a stable frame rate directly affects the game rhythm.

Special attention should be paid to the sound design - it is detailed and functional. Each type of surface has its own response: a step on metal, gravel, or stone is easily distinguished by tone and range. The sounds of weapons are worked out with engineering precision - you can hear not just a shot, but also the nature of the mechanism: the presence of a silencer, the vibration of an energy rifle, or a low-frequency hum when reloading. This creates a map by which an experienced player can determine the direction and type of threat. But, unfortunately, the sound of footsteps will never let the player understand the intentions of other raiders.

Ambivalence of Human Relations

One of the most unusual features of ARC Raiders was not so much the structure of the raids, but how the community was formed around it. Long before the release, journalists and game bloggers identified the project as a "family friendly extraction shooter" - a kind of alternative to hardcore competitors like Escape from Tarkov. It was this image that became the key marketing advantage of the game. For many players tired of constant tension, loss of equipment, and the aggressive atmosphere of Tarkov, ARC Raiders looked like a safe and friendly platform - a place where survival does not imply total hostility.

In practice, this approach worked: the ARC Raiders community really turned out to be unusually peaceful for the genre. In most raids, you can find random players pursuing their own goals - complete a task, collect resources for the ark, get parts for a workbench or augmentations. And contrary to the usual logic of extraction shooters, many of them prefer not to shoot. When meeting, players often use the command wheel or voice chat to offer peace, ask for help, or exchange resources. In half of the cases, these proposals are actually fulfilled. Raiders unite, accompany each other to the evacuation point, and jointly complete missions. For a genre where any interaction usually ends in death, this is a rare phenomenon.

However, this phenomenon has a downside. The game system does not distinguish between altruism and aggression, which means that both styles of behavior exist in parallel. In the same 50% of cases, the meeting ends in battle. Someone shoots first out of caution, someone simply checks the reaction of the enemy. The paradox is that all players here belong to the same faction - formally, they are allies fighting for a common cause. But the in-game logic does not limit internal conflicts in any way. Such clashes are dissonant with the idea of an "extraction adventure" - a journey through a hostile world where people should help each other.

As a result, the project became an arena for a social experiment. Some players really follow the unspoken code of mutual assistance, others deliberately destroy trust. Some ingratiate themselves into an alliance, and then betray their partners, others set up ambushes at the exits, and still others commit real war crimes - mining the bodies of fallen raiders. In most games of the genre, this is simply technically impossible, but here the mechanics of mines and traps allow you to implement such scenarios!

The motives of such players are different: someone compensates for past defeats, someone tries to impose on people the ideology of total hostility to each other, and someone dreams of seeing the world in flames.

The main problem is that the game does not regulate such behavior in any way. In Escape from Tarkov, killing allies reduced reputation and karma: the character lost the trust of merchants, and in extreme cases, a special Boss - Partisan - began to hunt him. There is nothing like this in ARC Raiders. The game does not distinguish between good and evil. Moreover, treacherous killings can be beneficial: by taking the resources of an ally, you accelerate the development of your own shelter. Thus, the system inadvertently encourages aggression, although it was originally promoted as a space for cooperation.

Interaction problems are not limited to the moral side. They are also manifested in the structure of raids. The tasks themselves do not contribute to interesting cooperation: these are standard tasks of the level "collect", "deliver", "scan". The main emphasis is placed on PvE activity, which is logical, given the original idea of the project. But the lack of complex and complex missions makes the joint passage mechanical - players simply run from point to point, avoiding risk.

Despite the simplicity of the story quests, which end very quickly, the game from time to time still forces raiders to engage in battle. This happens through random tasks that appear directly during the raid. Sometimes you will be given tasks to inflict damage on other raiders from a certain weapon, and the reward for such activities is Battle Pass coins, used to unlock cosmetic items and useful equipment.

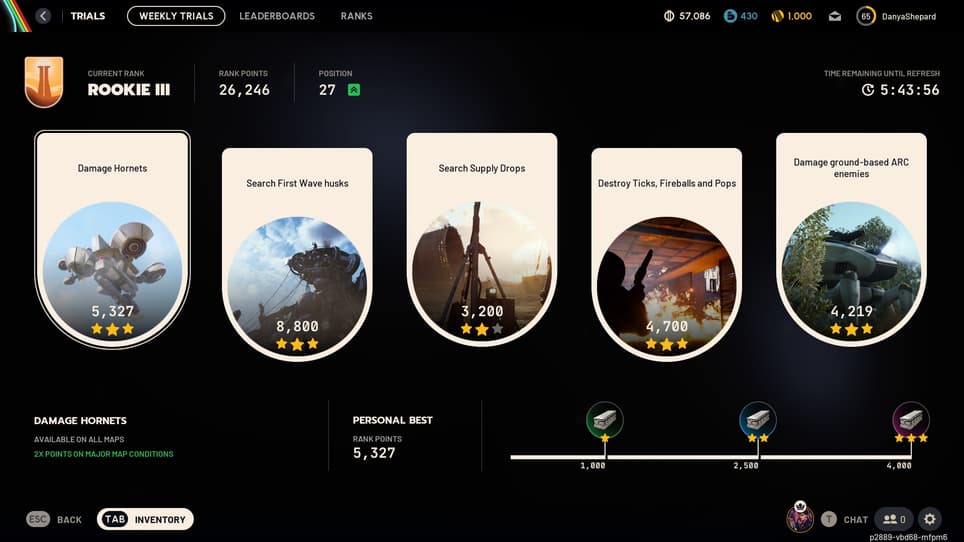

A separate direction is represented by weekly challenges, which form the basis of long-term progression. ARC Raiders has its own ranking table, where players advance through completed tasks. However, unlike classic multiplayer games, here the developers deliberately abandoned direct competition between participants. Promotion through the rank is built not on killing other players, but on performing tasks of a peaceful nature: collecting resources, destroying machines, or exploring objects.

An additional dissonance is created by the mechanics of "free" raids. Here you can go on a mission with pre-issued equipment, complete tasks, and gain experience - unlike most analogues, where such sorties serve only as training and a safe way to find resources. This removes financial and material risk, but does not devalue success in case of leaving the raid.

Added to this is an unstable player selection system. The game can connect you to both a new raid and an already ongoing one, without warning. In one case, you get into an empty location with a minimum of resources, in the other - into an area where the battle is nearing its end. Because of this, one raid can be visited by up to 100 people. For players using personal equipment, this creates a feeling of a pointless waste of time: the risk of loss remains, and the reward is often absent. At the same time, the constant replenishment of the raid with new participants increases the frequency of random collisions, making the behavior of other players even less predictable.

Group raids partially solve this problem. The squad can consist of up to three people, but in such conditions the level of trust is reduced to zero. It is extremely difficult to negotiate with groups, which is why the squad has to prepare for unexpected attacks and choose a position for a successful ambush. In this mode, cooperation turns into a kind of Royal Battle of small scales, where the winner is not the one who shoots first, but the one who enters the battle last. The latter get the opportunity to finish off weakened opponents and take all the loot.

Diagnosis

The overall impression of ARC Raiders remains contradictory. On the one hand, this is certainly an attempt to make its extraction shooter as accessible and humane as possible. On the other hand, the game demonstrates that simplifying mechanics and betting on social interaction does not always lead to the expected result.

ARC Raiders is a fat-free version of Escape from Tarkov, where realism, aggression, and moral sanctions have been removed from the hardcore formula, and community interaction has been brought to the fore. The developers managed to build a whole ideology of friendliness in the extraction shooter, where the priority is not killing, but joint exploration of the world, collecting resources, and fighting robots. The advertising campaign skillfully consolidated this image, and many really believed that a benevolent community could exist in an aggressive genre.

Therefore, ARC Raiders has turned into a social experiment, and not into a sustainable gaming ecosystem. Peaceful interaction turned out to be possible, but not mandatory. There are no rules, no punishments either - and each player decides for himself who he will be: an ally, an observer, or a traitor. This has led to a state of anarchy, where the community lives on the principle of self-regulation. No one is responsible for order, and the maximum consequences that await the violator are a counter shot and the loss of the collected loot.